Our ability to act against the climate emergency will determine a range of possible futures outcomes, but ultimately it is a choice between continuing with “business as usual” or taking direct measures toward a future in which global warming will be contained to below 2 °C. Human health and societal stability are intrinsically linked to the changing climate, therefore, the effectiveness of policies implemented in the next decade will have far-reaching effects in determining these global eventualities.

While there is still time to act, a recent study published by doctors in the 2019 report of The Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change has determined that the worst effects of a warming planet will hit society’s youngest members the hardest, impacting their health from infancy to old age.

“The life of every child born today will be profoundly affected by climate change,” the authors state in the report. “Without accelerated intervention, this new era will come to define the health of people at every stage of their lives.”

The report is an independent collaboration between 35 academic institutions and UN agencies from all over the world, representing the work and consensus of scientists, engineers, energy, food and transport experts, economists, and health professionals. The report tracks 41 indicators of climate health risk across a range of sectors including vulnerability to extreme events such as flooding, drought, wildfire risk, and mosquito-borne diseases, as well as public and political engagement, adaptation planning, and mitigation actions.

Even with a growing demand for change, as seen in global political movements such as Fridays for Future, the authors of the report suggest the world is currently following the business as usual pathway, as evident in a 50% increase in global fossil fuel consumption over the last three years and the total primary energy supply from coal increasing by 1.7% between 2016 and 2018, reversing a previously recorded downward trend.

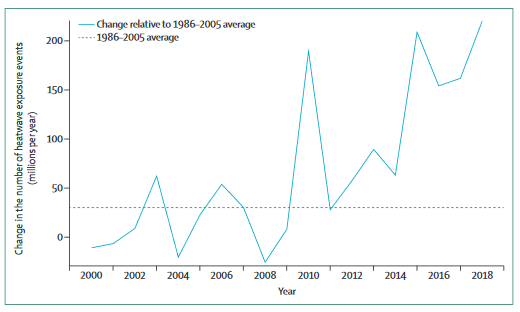

Perhaps the most immediate impact of a changing global climate on human health is seen in the increased frequency, intensity, and duration of heat extremes. Populations aged 65 and older are currently the most vulnerable. However, children are also at risk as they are less capable of adapting to temperature extremes, which, according to the study, leads to a greater risk of electrolyte imbalance, fever, respiratory disease, and kidney disease.

Children are also the most susceptible to the potentially permanent effects of malnutrition as a result of the limited access, availability, and affordability of food. Improvements in nutrient and water management have resulted in increases in global food production, however, the number of undernourished people worldwide has been increasing since 2014. Rising temperatures are reducing the length of growing seasons, flooding and drought are leading to a loss in agricultural land, and rising sea levels threatens fisheries and aquaculture—fish provide almost 20% of animal protein intake for 3.2 billion people.

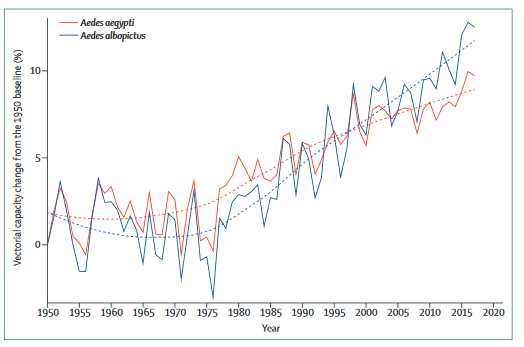

Climate change has also been found to enhance the transmission of some infectious diseases—dengue, malaria, Vibrio cholerae and other pathogenic Vibrio species (pathogens responsible for part of the burden of diarrhoeal disease)—to which children are the most susceptible.

“Trends in climate suitability for disease transmission are particularly concerning, with 9 of the 10 most suitable years for the transmission of dengue fever on record occurring since 2000. Similarly, since an early 1980s baseline, the number of days suitable for Vibrio has doubled, and global suitability for coastal Vibrio cholerae has increased by 9.9%.”

With increased urbanization comes highly concentrated populations living in cities (70% global urbanization is expected by 2050), resulting in higher rates of emissions and fine particulate matter pollution.

“Few cities worldwide have achieved [fine particulate matter concentrations] that are below the WHO guideline,” the study states. “In 2016 there were 2.9 million premature deaths globally that were associated with ambient [air] pollution, with minimal improvement in global mortality from 2015.”

Air pollution from fossil fuels causes chronic damage to our vital organs. This means that with an ever-increasing global demand for energy and a slow shift toward renewables, future generations (as well as the current population) will have to deal with the damaging, cumulative effects that microscopic particulate matter will have on their health and life span.

Finally, although more difficult to quantify, the social and political downstream effects of climate change, such as migration, poverty exacerbation, and violent conflict, are predicted to worsen. Many studies have also explored the growing effects climate change is having on the mental well-being of young people, who report high rates of anxiety, depression, and angst as the effects of global warming become more apparent and their future appears bleak.

The authors do say that although the effects of the crisis will be dire, there is still time to act to avert some of the most severe health consequences they reported.

“The Paris Agreement has set a target of ‘holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1·5 °C.’ In a world that matches this ambition, a child born today would see the phaseout of all coal in the UK and Canada by their sixth and 11th birthday; they would see France ban the sale of petrol and diesel cars by their 21st birthday; and they would be 31 years old by the time the world reaches net-zero in 2050, with the UK’s recent commitment to reach this goal one of many to come,” the authors report. “The changes seen in this alternate pathway could result in cleaner air, safer cities, and more nutritious food, coupled with renewed investment in health systems and vital infrastructure.”

However, they go on to say that while such a transition is beginning to unfold, the world is yet to see a response from governments which matches the scale of this crisis.

As our knowledge of the long-term health consequences of climate change increases, so too does our need to protect people, especially those most vulnerable. Unfortunately, some future outcomes are currently unavoidable and require immediate adaption and planning to be able to minimize harm. These include national adaptation plans for health and climate monitoring systems, as well as an immediate shift away from carbon-based fuels to mitigate current heating trends.

“Bold new approaches to policy making, research, and business are needed in order to change course. An unprecedented challenge demands an unprecedented response, and it will take the work of the 7·5 billion people currently alive to ensure that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate.”