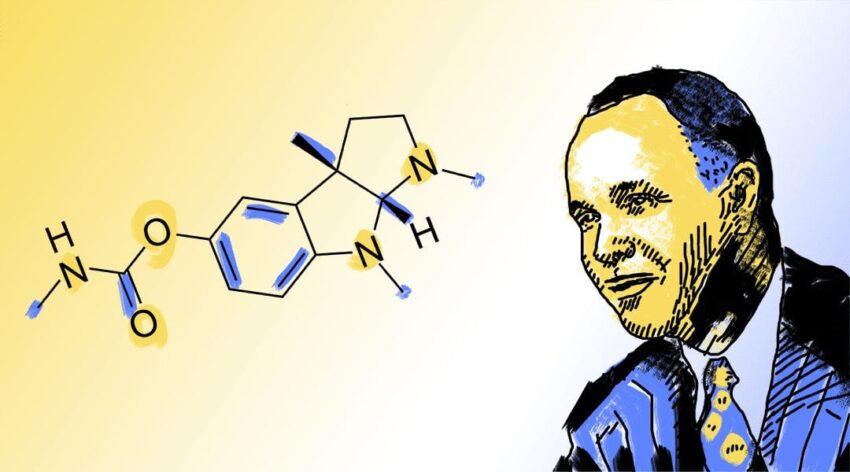

Image credit: Kieran O’Brien

Percy Julian was an American natural product chemist who pioneered the development of steroid-based therapies still used today. His research led to the synthesis of drugs to treat glaucoma and arthritis, and although his race presented challenges at every turn, he is regarded as one of the most influential chemists in American history.

In a biographical memoir published by the National Academy of Sciences in 1980, when talking about his life and the many obstacles he faced, Julian is said to have connected his “long and arduous climb” with a verse from Donald Adams’ poem, The Seventh Fold:

“My dear friends, who daily climb uncertain hills in the countries of their minds, hills that have to do with the future of our country and of our children, may I humbly submit to you, the only thing that has enabled me to keep doing the creative work, was the constant determination: Take heart! Go farther on!“

It was this drive to “go farther on” that helped him push back against unjust societal norms and carve out a place for himself among science’s most influential and inspiring contributors.

Early life and education

Born in Montgomery, Alabama in 1899, Julian was the eldest of six children belonging to Elizabeth Lena Julian Adams, a teacher, and James Sumner Julian, a railway postal clerk. His grandparents had been slaves and he faced many obstacles throughout his life as a result of his race, which made life difficult for Black Americans.

At the time in Alabama, high school was not available to members of the Black community, and after the eight grade most had to abandon education — but Julian had higher hopes.

His father is said to have had a love of math and philosophy, which inspired his son. He also held a federal government position, which helped elevate his status and provided a stepping stone for Julian to obtain a formal college education.

In 1916, at the age of 17, Julian applied to DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana, which had limited slots for African-American students who lived off-campus due to race segregation laws.

In the biographical memoir, he’s noted as saying: “On my first day in college, I remember walking in and a white fellow stuck out his hand and said, ‘How are you?—Welcome!’ I had never shaken hands with a white boy before and did not know whether I should or not. But you know, in the shake of a hand my whole life was changed, I soon learned to smile and act like I believed they all liked me, whether they wanted to or not.”

He was inadequately prepared for college and so enrolled as a sub-freshman until his senior year, which required he take high school-level courses in the evenings to catch up with his peers. He also had to work to help pay for his expenses, but nevertheless excelled, graduating first in his class in 1920 with Phi Beta Kappa honors.

Later, the entire Julian family moved to Greencastle, where all of his siblings, including his sisters Mattie, Irma, and Elizabeth, graduated from DePauw University.

Life in academia

After completing his college degree, Julian wanted to obtain his doctorate in chemistry, but this was not immediately possible as these opportunities were again limited for African Americans. In the meantime, he took a position as chemistry instructor at Fisk University in Nashville, and in 1923, was able to attend Harvard on an Austin Fellowship to complete his Master’s, where he worked with Professor E. P. Kohler on the chemistry of conjugated systems.

Again, he faced a traumatic disappointment when Harvard would not allow him to pursue his doctorate due to his race. Between 1923 and 1929, he worked at predominantly Black institutions — first at West Virginia State College and then as head of department at Howard University. In 1929, Julian won the Rockefeller Foundation grant, allowing him to finally earn his doctorate at the University of Vienna, studying natural product synthesis with Ernst Späth.

In 1931, he returned to his position at Howard University, but after two years was forced to leave following a number of personal scandals, including having personal letters published in newspapers and being accused of having an affair with his future wife while she was still married to one of his colleagues. Julian was forced to resign and in essence, lost everything he had worked for.

World renowned chemist

It was at this time that his previous mentor, Professor William Blanchard, helped him to return to DePauw University as a research fellow.

In 1935, in collaboration with his friend and assistant Josef Pikl, Julian completed an 11 step total synthesis of the anti-glaucoma drug physostigmine, originally isolated from the Calabar bean. There was a bit of controversy as Sir Robert Robinson of Oxford University had already published an earlier synthesis of physostigmine, which Julian found to not be correct.

This was before chemists could rely on sophisticated tools such as nuclear magnetic resonance or X-ray crystallography to identify molecular structures. Julian noticed that the melting point of an intermediate compound reported by Robinson (d,l-eserethole) did not match the literature, indicating he had in fact not made it. Putting his own reputation on the line, Julian published a paper reporting Robinson’s error and the correct synthesis, stating:

“To our surprise, our d,l-eserethole exhibited entirely different properties than those of a compound synthesized by Robinson and his coworkers and called d,l-eserethole. Likewise were all derivatives different.

“Inasmuch as our (optically) inactive material subjected to characteristic reactions of eserethole of natural origin yielded perfectly analogous results, we expressed the belief that our product was the real d,l-eserethole and that of the English chemists must be assigned another constitution. This is now proved conclusively by synthesis of l-eserethole, identical with the product of natural origin.”

This would establish his reputation as a world-renowned chemist, as even 65 years later his achievement led to derivatives that have enhanced our ability to treat glaucoma and have shown promise in other therapeutic areas, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

He gained further recognition with his inroads into steroid chemistry, which occurred after isolating crystals of stigmasterol from the same Calabar bean. Stigmasterol contains a series of fused rings that make it a viable precursor to a number of important steroids, such as the sex hormones used in birth control, estradiol and testosterone.

At the time, Julian hoped that stigmasterol could serve as a starting point for the synthesis of human steroidal hormones, laying the groundwork for further therapeutic investigation of these molecules.

Later life and career

In 1936, Julian was denied a faculty position at DePauw University due to his race, and so sought opportunities elsewhere. A major blow was dealt when the chemical company DuPont offered a job to Pikl but retracted the offer to Julian because they were unaware he was Black. Another job fell through because the town where the company resided had a law forbidding African Americans to be housed overnight.

He eventually obtained a position with Glidden in Chicago as director of research for soya products. After a serendipitous accident involving water seeping into a soy bean oil drum causing the precipitation of a white solid, Julian was able to isolate sterols from the oil. Over the course of 18 years of research, Julian produced numerous successful products and patents including Aero-Foam, a foam derived from soy protein that was used to put out oil and gas fires and was widely used in World War II.

His research direction later changed, shifting to the production of human steroids, such as progesterone and testosterone, from plant sterols, and for which medical researchers were discovering a range of new medicinal applications. Their availability was a significant problem as only small quantities could be isolated from natural sources. Julian’s work enabled their production on an industrial scale, helping promote research in this area and lowering the cost of hormonal treatments.

Most notably, Julian and his team developed an efficient route to Reichstein’s Substance S, used in the production of hydrocortisone and its derivatives, which are used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

After 18 years, Julian left Glidden to found his own research firm, Julian Laboratories, Inc, which specialized in the production of synthetic cortisone. He sold his company in 1961 for more than $2 million, and later formed a nonprofit research institute called the Julian Research Institute.

Among his many achievements, he was elected to the National Academy of the Sciences in 1973, was elected to the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 1990, and in 1999, his synthesis of physostigmine was recognized by the American Chemical Society as one of the top 25 achievements in the history of American chemistry.

He was also a vocal human rights advocate, facing not only insurmountable odds to pursue a career as a chemist, but also personal violence because of his race. In 1950, Julian’s career allowed him to purchase a home in a white suburb of Chicago called Oak Park. When he and his family arrived, they found the house had been bombed by people opposed to having Black Americans move into the community. His home was attacked again in June of 1951.

In spite of this, Julian and his family would not be intimidated. He helped push for social progress by hiring scientists of color at his company and spoke out against the barriers that racism created for him.

Reflecting on his career after retirement, Julian said: “I feel that my own good country robbed me of the chance for some of the great experiences that I would have liked to live through. Instead, I took a job where I could get one and tried to make the best of it. I have been, perhaps, a good chemist, but not the chemist that I dreamed of being.”

Julian continued as a private researcher and served as a consultant to major pharmaceutical companies until his death on April 19, 1975.

Read more Pioneers in science articles >>

References:

National Academy of Sciences, Percy Lavon Julian, A biographical memoir by Bernhard Witkop. http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/julian-percy.pdf (Accessed November 23, 2020).

American Chemical Society National Historic Chemical Landmarks. Percy Julian: Synthesis of Physostigmine. http://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/julian.html (November 22, 2020).