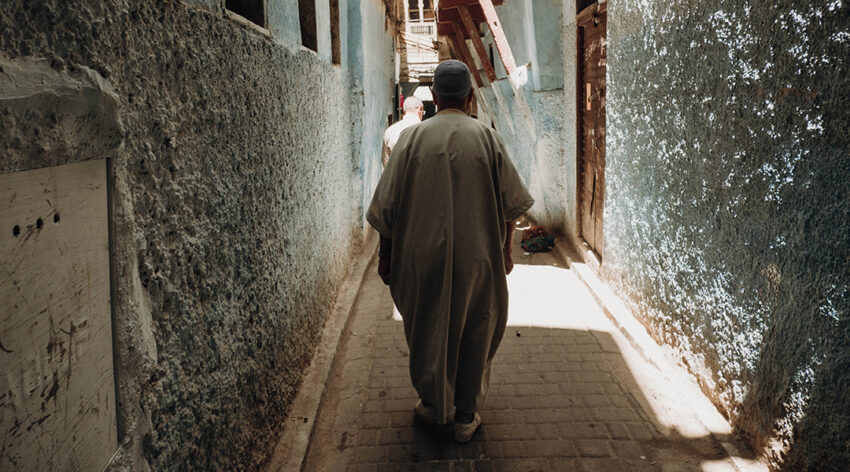

A resident walks the streets of Fez, Morocco, UNESCO World Heritage Site. Image credit: Chrissie Giannakoudi Unsplash

Tucked away in a remote Indonesian cave lies a key component in the evolution of human expression: a painting of a pig. The cave painting is the world’s oldest rendering of a figure and dates back over 45,000 years, offering a valuable peek into the lifestyle and customs of the people who painted it. This finding was a monumental discovery for anthropologists, but there is one lingering force threatening to erase these artifacts from existence. The rising frequency of consecutive dry days as a result of droughts followed by heavy monsoons have accelerated the build-up of salts within the cave systems housing the rock art, causing them to disintegrate at an alarming rate. This remnant of human heritage is in peril.

But heritage is more than just cave paintings. It is an evolving resource that supports social cohesion, strengthens well-being, and at times, provides a life line to impoverished communities.

Much of the conversation around climate change tends to focus on environmental threats and their direct impacts on the stability of society. However, its relationship to both the tangible and intangible elements of our shared history and culture is often overlooked, though they are no less important.

“Our cultural heritage underwrites us, it defines our sense of identity, memory, and community,” said John Hughes, researcher at the University of the West of Scotland. “If we lose our heritage, we lose a large part of ourselves.”

Hughes and his colleagues have been exploring the connection between human heritage and the changing global climate. “Since 2004, scientists and heritage professionals have been studying the effects of climate change on our cultural assets,” he said. “They raised the alarm that these irreplaceable witnesses to our past are being lost — in some cases at alarming rates. This should be a concern to all of us.”

As stronger storms, wildfires, flooding, loss of land due to rising sea levels, and desertification affect the lives of millions of people — instigating political instability and forced displacement in some cases — climate change is also degrading elements of our history, often right before our eyes.

In the Russian Altai mountains, melting permafrost is leading to a loss of frozen tombs, or kurgans. This area is a famous burial ground, dubbed the “Treasures of the Pazyryk Culture“, and contains heaps of intact buried artifacts, bodies, and rock carvings from the Scythian nomadic culture, which prospered 2500 years ago. As warming global temperatures lead to loss of permafrost, deterioration of the once preserved organic material and structural damage as a result of the associated ground movement will accelerate the loss of this invaluable ancient burial site.

“Losing these tangible elements of our heritage can also lead to a loss of the intangible: traditions, rituals, community celebrations,” explained Elena Sesana, architect and researcher at the University of the West of Scotland, and lead author of a study exploring this topic recently published in WIREs Climate Change. “If repeated droughts, floods, or rising sea levels result in a community moving away from its roots — perhaps also breaking it up — their traditions may also be destroyed.

“The issue that we face now and into the future is that the frequency and intensity of previously gradual degradation processes are changing. These conditions are becoming more threatening, and the harsh reality is that sometimes the race to save these heritage assets is a race we are bound to lose.”

While scientists try to preserve or record these treasures before they are lost, many are asking what greater role these cultural assets can play in developing adaptation strategies and in raising awareness to the urgency of climate change.

“Considering the wider picture, even wider than the embodied educational, scientific, and social value of cultural heritage, these assets are also being increasingly appreciated for the role they can play in contemporary sustainability agendas,” said Chiara Ciantelli, researcher at the Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development.

This may sound less intuitive than direct measures to remove carbon from the atmosphere, but elements of cultural heritage can be used as a focal point for community resilience, as well as for the drive and development of future adaptation strategies.

In 2015, the role of culture and heritage in sustainable development was recognized by the United Nations (UN) in its 2030 Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals. One of the clearest examples addresses “harnessing the potential of heritage to eradicate extreme poverty” by leveraging heritage (in all its forms) to create sustainable livelihoods as well as reduce vulnerability to climate-related economic, social, and environmental shocks by integrating heritage and Indigenous knowledge in community planning and services.

This might seem lofty, but a report published by the ICOMOS working group outlined a case study involving the Medina of Fez UNESCO World Heritage Site, an old walled area in the city of Fez founded in the 9th century and which houses the world’s oldest university. Some of the most serious issues facing the site included deteriorating residential zones, degradation of the infrastructure, and environmental pollution.

Over the past 40 years, a number of rehabilitation projects involving government, religious, and civic leaders, along with merchants, artisans, householders, renters, and many others contributed ideas for possible development and worked toward consensus on interventions and strategy that ranged from the restoration of historic monuments and buildings to housing units threatening to collapse. The initiative had two priorities: the safety of the human lives and the safe-guarding of cultural heritage and traditional constructions.

The project became profitable for the population, driving tourism and improving quality of life. Quality of housing and the environment were also substantially improved thanks to public investment in solid waste management, infrastructure, and urban facilities. There were both positive and negative takeaways from this case study, but leveraging a connection to community’s culture made progress possible while also enhancing their identity and sense of belonging. This in turn led to positive changes such as better standard of living and sustainable job opportunities and livelihoods that would carry them forward.

“The potential effects on the vast collection of assets we call heritage are complex, wide ranging, and often unpredictable,” said JoAnn Cassar, head of the Department of Conservation and Built Heritage at the University of Malta. “However, once it is clear in the minds of all those who own, work with, or simply live alongside a historic building, a museum, a cathedral or temple, an archaeological site or a traditional village that these are real and current threats, more informed decisions about possible courses of action will be possible.”

There are many examples of similar scenarios from which we can learn about adaptation to the inevitable impacts of climate change. In addition to making a community more resilient, these efforts can incorporate elements of climate action by identifying and promoting the use of local resources, incorporating new technologies to balance heritage-based knowledge to achieve energy efficiency and reduce carbon emissions.

“We recommend that multiple pathways to change are taken into consideration when planning adaptation strategies for managing heritage” said Alexandre Gagnon, senior lecturer in geography (climate change) at Liverpool John Moores University. “Besides, there is a notable lack of research on such impacts in certain areas of the globe, especially in Africa, Asia, and Central and South America, which urgently needs to be addressed. To date most research has been concentrated in the more affluent global North, despite the wide acknowledgement that it is in the South [where] impacts will be felt most.”

The role of heritage in plotting a pathway towards inclusive, transformative, and just climate action is linked to better protection of such resources. There is a need for urgent, collective action to safeguard heritage from climate change through a precautionary approach that pursues pathways for limiting global warming to 1.5 °C.

“We want to preserve our artistic and cultural heritage,” said Sesana. “We hope that our extensive review, which builds on many previous studies, can stimulate further work, provide a sound, factual basis and raise awareness at all levels of society to enable decision and action, not only for the protection of our shared heritage, but also for the benefit and safeguarding of humanity’s history and identity.”

Reference: Elena Sesana, et al., Climate change impacts on cultural heritage: A literature review, WIREs Climate Change (2021). DOI: 10.1002/wcc.710