An intriguing thought experiment catalogs which of our interstellar neighbors might be gazing back at us.

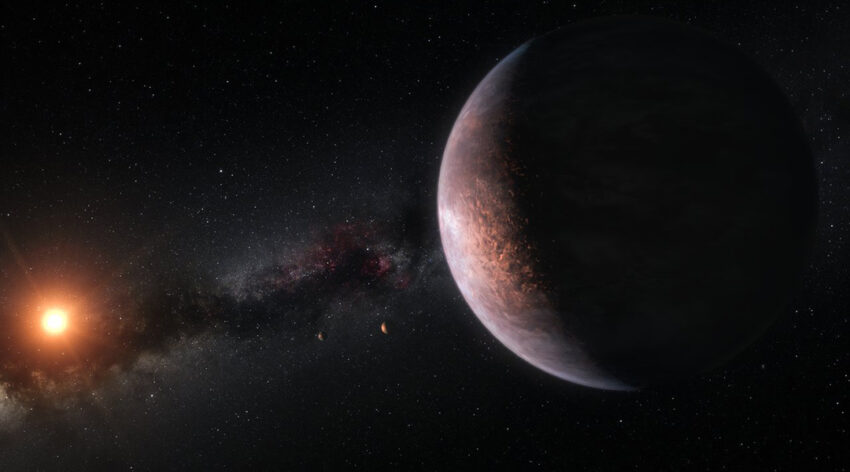

Artist’s impression of the planets orbiting the red dwarf star TRAPPIST-1. Image credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser

“Are we human because we gaze at the stars, or do we gaze at them because we are human? Pointless, really…’Do the stars gaze back?’ Now, that’s a question.” Fans of the movie Stardust might be familiar with this opening line, but new findings from scientists at Cornell University and the American Museum of Natural History have made it sort of true.

In their new study, the researchers put together a list of 1,715 star-systems within 100 parsecs or 326 light-years away that could have observed Earth by watching it “transit” or cross in front of our Sun. This seems a logical assumption given that 70% of exoplanets have been identified this way using telescopes on Earth.

When a planet passes in front of its host star, scientists can glean a host of information from variations in its spectral signature, allowing them to determine the chemical composition of its atmosphere. This requires very precise alignment between the transitioning planet, its star, and our Sun for it to be detectable.

Extensive efforts are being put into the search for exoplanets, with the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope set for later this year — it will be one of the most powerful telescopes orbiting Earth capable of making detailed observations of exoplanet atmospheres in order to search for extraterrestrial life — and the Breakthrough Starshot initiative’s miniature-sized spacecraft being sent to the closest exoplanet located in orbit around Proxima Centauri — 4.2 light-years from Earth — to fully characterize that world.

But what if inhabitants of an alien world have already spotted us?

“From the exoplanets’ point-of-view, we are the aliens,” said Lisa Kaltenegger, professor of astronomy and director of Cornell’s Carl Sagan Institute, in the College of Arts and Sciences, in a statement. “We wanted to know which stars have the right vantage point to see Earth, as it blocks the Sun’s light. And because stars move in our dynamic cosmos, this vantage point is gained and lost.”

Using the European Space Agency’s Gaia eDR3 satellite data, Kaltenegger and co-author Jackie Faherty, a senior scientist at the American Museum of Natural History, cataloged which stars enter and exit the Earth Transit Zone within a 10,000 year time span, and for how long. “Gaia has provided us with a precise map of the Milky Way galaxy,” Faherty said, “allowing us to look backward and forward in time to see where stars had been located and where they are going.”

313 stars were correctly positioned within the last 5000 years, roughly when human civilization began, and an additional 319 will enter this vantage point in the future, while 1,402 of this number have been in the Earth’s Transit Zone for a significant amount of time.

The astronomers also identified a subgroup of 75 stars located within 100 light years of Earth that would have been primly located to receive transmitted radio waves from Earth, which we began broadcasting within the last 100 years.

“Our analysis shows that even the closest stars generally spend more than 1,000 years at a vantage point where they can see Earth transit,” Kaltenegger said. “If we assume the reverse to be true, that provides a healthy timeline for nominal civilizations to identify Earth as an interesting planet.”

The Ross 128 system, for example, is a red dwarf star system with an Earth-sized exoplanet located about 11 light-years away. Any inhabitants could have seen Earth transit our own sun for 2,158 years, starting about 3,057 years ago — though they lost their vantage point about 900 years ago. Kaltenegger and Faherty also highlight the Trappist-1 system, 45 light-years from Earth, in which four exoplanets have been discovered within the temperate, habitable zone of the system’s host star. While we can see them, they won’t be able to observe us for another 1,642 years.

Timing is everything it seems, and this study provides in interesting and alternative perspective to our search for life on other planets. “One might imagine that worlds beyond Earth that have already detected us, are making the same plans for our planet and solar system,” said Faherty. “This catalog is an intriguing thought experiment for which one of our neighbors might be able to find us.”

Reference: Lisa Kaltenegger and Jackie Faherty, Past, present and future stars that can see Earth as a transiting exoplanet, Nature (2021). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-03596-y

Quotes adapted from press release provided by Cornell University