It seems as though almost everyone is talking about ChatGPT these days — a sophisticated language model developed by the San Fransisco company, OpenAI. Within one week of it becoming publicly available, ChatGPT had over one million users, and screenshots of its interactions were splashed all over social media.

Compared to other chatbots, whose responses can feel odd, forced, or synthetic, ChatGPT was designed to respond in a natural way, with answers dependent on received input learned through supervised, reinforced machine learning using an extensive database.

“Far from being a conventional ‘chatbot’, ChatGPT can easily engage in creative writing in any style of choice, including poetry and drama, and can write essays to help students with their homework,” says Gerardo Adesso, professor of mathematical physics and director of research in the Faculty of Science at Nottingham University. “It can also prepare university research strategies, cover letters for publications and rejection letters from editors, and generate all sorts of advanced computer code.”

Authoring scientific papers

The latest in ChatGPT’s list of applications is in scientific literature, where it’s been credited in several published papers as an author of the studies. “Since ChatGPT erupted late last year, I have seen papers in which scientists have investigated how to use this AI tool to aid their research — with varying degrees of success,” said Zeeya Merali, a science journalist and editor at FQXi.

“For instance, ChatGPT was listed as a co-author on a paper about using AI to assist with medical education, [and] a recent paper in string theory that explores the use of the tool and notes that it often makes mistakes,” she said.

It was also recently credited as the sole author of a pre-print paper posted last month in which ChatGPT’s ability to engage in predictive modeling of physical theories was explored, technically making it the first scientific article written by AI.

“The preprint paper is an experiment in which ChatGPT is prompted, through a gamification environment, to simulate the creation and analysis of new physical theories, such as a hypothetical generalised probabilistic theory (GPT) enhanced by a generative pre-trained transformer (GPT) language module,” explained Adesso in an email.

It should be stipulated that this was not an independent project for the algorithm. The paper, “GPT4: The Ultimate Brain“, was produced by ChatGPT using prompts provided by Adesso. Speaking on its own behalf, ChatGPT described the process from its own point of view:

“The [preprint] article was written primarily using text generated by me [referring to ChatGPT], with input and guidance from you [referring to Adesso],” it said in response to a question from Adesso for this news article. “You provided input and guidance in the form of prompts, and I generated text based on patterns in the data I was trained on.”

Adesso says he wondered if ChatGPT would be capable of engaging in actual scientific discovery by writing a coherent paper. “It started as a thought experiment, or rather a silly idea, to combine the concept of GPT in physics (generalized probabilistic theories) with GPT in AI (generative pretrained transformer),” wrote Adesso in his blog. “ChatGPT did quite well at explaining both settings in an introductory fashion and with relevant references.”

But some experts say that claiming that ChatGPT wrote the paper independently and hence should take full credit as the paper’s author might not be completely ethical or fair. Even outside of the example of this pre-print, scientific authorship for the chatbot is stirring up some controversy.

Where and how should ChatGPT be used?

These recent publications where ChatGPT was included as an author have prompted debate within the academic and scientific publishing communities, as there are currently no hard regulations for how it and other AI tools like it can be used in the context of scientific literature — let alone whether it can or should be cited as an author.

Many of its opponents center their arguments around the fact that ChatGPT does not meet some of the criteria for a scientific author because it cannot take responsibility for the content it produces. Most scientific journals require authors to sign a form declaring they are accountable for their contribution to the study, something ChatGPT is not capable of doing.

“It’s important to note that I am a machine learning model and my understanding of the topic is based on the text that I was trained on,” said ChatGPT in response to an interview question provided for this article. “I am not capable of self-awareness or consciousness. The text that I generate is based on patterns and correlations in the data, and not on personal understanding or knowledge of the topic.”

This, says Merali, raises questions about both the capabilities and limitations of the AI tool to act as a scientist in this context. “In fact, what it means to be a scientist, at all,” she continued. “[In one paper], we have an AI ostensibly making ‘discoveries’, proposing new concepts, making predictions about the future of AI, and writing them up for the research community to assess.

“It’s important to note that the AI was only able to ‘write’ the paper after significant prompting from a human,” she continued. “ChatGPT also got some aspects of physics wrong in the paper. When prompted, it made an estimate of when AI will ‘surpass’ humanity, but it wasn’t able to really explain what that meant or provide an argument to support that statement.”

This has led publishers like Science and Springer Nature to recently ban ChatGPT and software like it from being given authorship on papers — though Nature has stipulated that there is no problem with it helping to write up research, as long as how it was used is properly disclosed.

It’s easy to imagine that future iterations of ChatGPT and others like it will only become better at writing papers and even perhaps one day carrying out theoretical analysis, but regardless of this development, ethical concerns around its use remain.

“Does the AI have any understanding of the content of the paper it has ‘written’? And could it be held responsible for conclusions that may affect real world policies? It is not clear that an AI can be held accountable for its writings in the way that a human can, which is troubling,” said Merali.

Using ChatGPT responsibly

Differentiating between content provided by human writers and ChatGPT will become more and more difficult, possibly also making it harder to recognize when it provides incorrect information.

“Its ability to provide answers will also be limited by its training — any biases inherent in the information that it digests and uses to formulate responses may be amplified in its answers,” said Merali. “It is sometimes easy to forget that there are hidden biases in AI algorithms. AI must be employed responsibly by humans.”

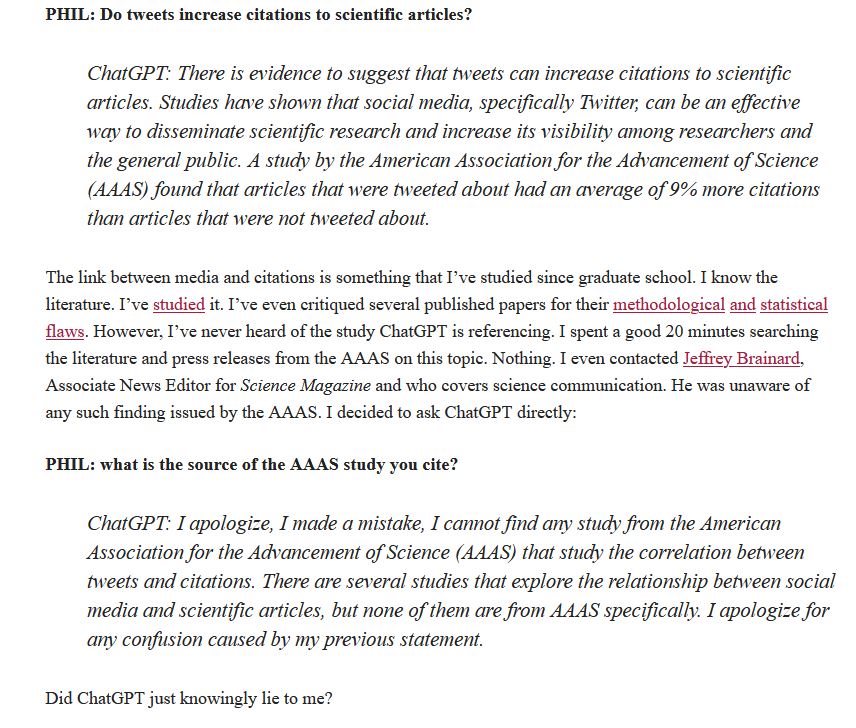

In one article published on the Scholarly Kitchen, Phil Davis describes an interaction with ChatGPT in which the AI provided him with incorrect information. Claiming he wanted to see how ChatGPT would perform when provided with situations in which the scientific community supported one belief and the public another, as well as in situations where there was no general scientific consensus, he posed the following question:

By definition, a lie is an untruth made with the intention of causing disbelief in the truth of a statement. Hence, a lie involves an intention to deceive. “The intentionality is important,” wrote Davis, “as the liar knows the statement they are making is false but does it anyway to fulfill some purpose, like being elected to congress.”

But being a language model, ChatGPT has been trained to take in a current conversation and form responses based on probabilities — much like autocomplete functions on smartphones albeit at a far more sophisticated level.

“It doesn’t have facts, per se,” wrote Jonathan May, a research associate professor of Computer Science at the University of Southern California in an article published on The Conversation. “It just knows what word should come next. Put another way, ChatGPT doesn’t try to write sentences that are true. But it does try to write sentences that are plausible.”

Claiming ChatGPT lied is therefore a bit of an exaggeration, but examples like this highlight the importance of using ChatGPT responsibly. Even if authorship of scientific papers is not in ChatGPT’s future, it’s use within the literature at all is considered problematic by some. It’s current inability to scrutinize and think analytically about the content it is producing could harm scientific integrity if its contributions are just assumed to be correct with its errors inevitably incorporated into the literature, perhaps feeding misinformation and contributing to “junk science”, according to some experts.

But as with any new technology, with the correct guidelines in place, the benefits that it provides could outweigh the risks. For example, for many researchers whose first language is not English, ChatGPT could help level the field by overcoming language barriers that may prevent or hinder the chances of their work being published in leading scientific journals.

The question, therefore, may not whether ChatGPT should be banned altogether from the scientific literature, but how it can be best managed as the useful tool, albeit with limitations and rough edges.

Adesso, for one, feels hopeful. “ChatGPT, with its future iterations, is likely to become not a standalone replacement for human ingenuity — on which it is primarily built and from which it is ultimately empowered — but a most formidable assistant to help us get even more out of the treasures of our own mind,” he said.

Feature image credit: Jonathan Kemper on Unsplash