A new way of reprogramming the body’s immune cells to seek out and eliminate cancer cells, acting as an internal cancer therapy.

Imagine that instead of requiring chemo- or radiation therapy, your body’s own cells could be alerted to the presence of cancer and directed to destroying it without any harmful side effects. Reprogramming our body’s cells to fight disease like this is a burgeoning area of research.

Progress has been made recently with a number of promising studies that have harnessed immune cells for this purpose, such as a personalized cancer vaccine that captures molecules from growing tumors or an anti-viral vaccine that targets the innate immune system for broader, longer-lasting effects.

Now, in a recent study published in the journal Advanced Science, researchers from the University of Bristol have reported a new way of reprogramming innate immune cells to seek out and eliminate cancer cells, enabling them to act as an internal cancer therapy.

Subverted immune cells

Innate immune system and its cells are a promising starting point for targeted internal therapies as they naturally serve as the body’s first line of defense, providing broad initial protection against all foreign bodies.

Innate immune cells, such as macrophages, have a unique surveillance capacity that enables them to detect rogue, pre-cancerous cells anywhere in the body. However, there is a slight problem: when innate immune cells encounter cancer cells, their initial task is often redirected to better serve the cancer, not the body.

“Our immune cells have a surveillance capacity which enables them to detect pre-cancerous cells arising at any tissue site in the body,” said Paul Martin, professor of cell biology in the School of Biochemistry at the University of Bristol and one of the study’s lead authors, in a statement. “However, when immune cells encounter cancer cells, they are often subverted by the cancer cells, and instead, tend to nourish them and encourage cancer progression. We wanted to test whether it might be possible to reprogram our immune system to kill these cells rather than nurture them.”

Martin and his colleague Stephen Mann, professor at Bristol’s School of Chemistry and the Max Planck Bristol Centre for Minimal Biology, sought to reprogram these hijacked macrophages to get them back to the task of fighting the cancer. The idea is to deliver a “reprogramming cargo” through artificial, cell-like micro-compartments called protocells.

“Steve and I were looking to do some experiments together that utilized his lab’s expertise in artificial protocells and my lab’s studies of inflammation in wound healing and cancer,” said Martin in an email to ASN. “Our first experiments together were designed to see whether we might use protocells to reprogram innate immune cells to make them do what we want them to do in a cancer scenario.”

The protocells the team developed were loaded with a molecule called anti-miR223, which binds and interferes with immune cells’ signaling machinery.

“The miniature, artificial protocells are taken up by the neutrophils and macrophages [white blood cells] just as they would take up a microbe or some other foreign particle,” explained Martin. “The ‘reprogramming’ cargo is an antiMiRNA, which specifically targets a signalling pathway in the white blood cells that normally dampens down their proinflammatory [cancer-fighting] state, so they are now [better] able to shrink cancers.”

Success in shrinking melanomas

Reprogramming inflammatory cells to clear early-stage cancer cells or to target and destroy a developed tumor has been a cancer therapy aspiration extending back to ancient bacteriotherapy anti-cancer treatments, wrote the team in their paper. This study is definitely a step in the right direction, with the scientists showing they were able to reprogram both animal and human immune cells in a way that should make them more “anti-cancer”.

“We show that this strategy works, not just in a dish but in a real organism; the injected protocells are taken up by inflammatory cells, and this leads them to be ‘reprogrammed’, which in turn leads them to shrink the melanomas [a type of skin cancer] in zebrafish,” said Martin.

“Neither Steve nor I are clinicians, so this is a basic science study, but through a collaboration with a colleague in Bristol, Ash Toye, we have tested whether similar reprogramming can be achieved in human white blood cells and the answer is yes, so this might indeed be a potential anti-cancer therapeutic strategy, and pre-clinical trials would be the next step.”

Reference: Paco López-Cuevas, et al., Macrophage Reprogramming with Anti-miR223-Loaded Artificial Protocells Enhances In Vivo Cancer Therapeutic Potential, Advanced Science (2022). DOI: 10.1002/advs.202202717

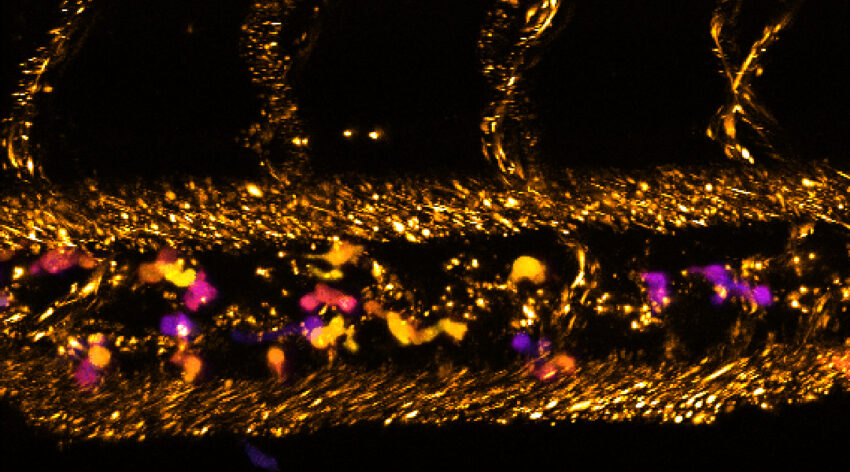

Feature image: Confocal image of a two-day-old zebrafish larva that received intravenous injection of protocells (small dots represented in “gold” color)