The ways astronauts prep for spaceflight could benefit cancer patients, researchers say.

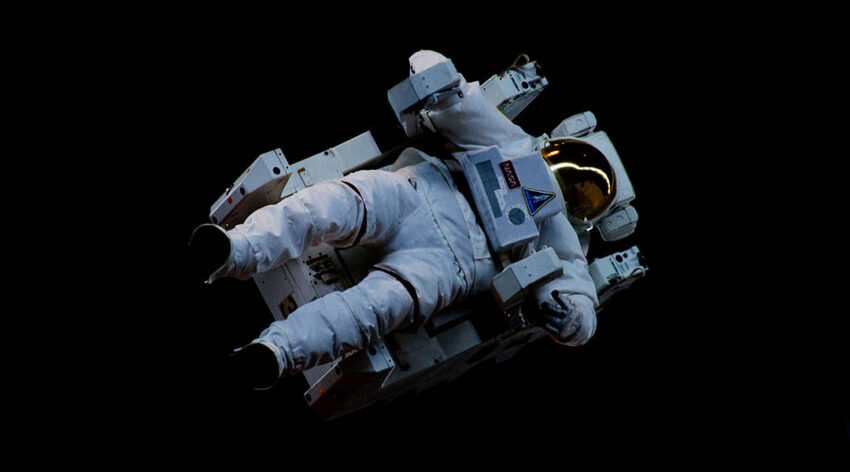

A recent commentary published in the journal Cell has found that astronauts and cancer patients experience similar physical stress, leading researchers to believe that the ways in which astronauts prepare for and recover from spaceflight could be beneficial to patients undergoing treatments such as chemo- and immunotherapies.

The study was carried out by researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. In a press release, the study’s senior author, Jessica Scott, an exercise physiology researcher at the center’s Exercise Oncology Service commented: “It was surprising when we looked at similarities between astronauts during spaceflight and cancer patients during treatment. Both have a decrease in muscle mass, and they have bone demineralization and changes in heart function.”

She also added that these similarities also extend to brain function. “Astronauts may get something called space fog, where they have trouble focusing or get a little forgetful. That’s very similar to what some cancer patients experience, which is called chemo brain.”

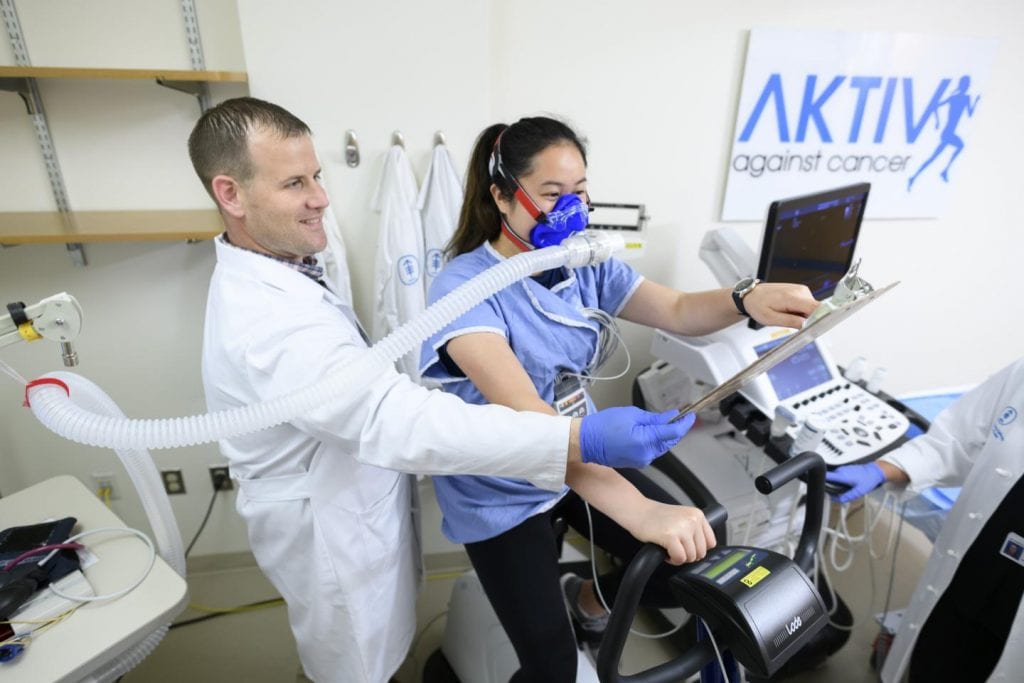

The past 40 years have witnessed remarkable advancements in cancer treatment, however, despite enormous resources being spent toward drug development the characterization and reduction of drug toxicity has remained largely unchanged, the authors say. In addition, monitoring and evaluating major organ function during “stress conditions” (i.e., treatment) is not common practice for oncologists. And in contrast to a number of other recommended recovery strategies for chronic diseases, a structured exercise regime is not recommended for cancer patients. In fact, cancer patients may still be advised to rest in preparation for and during treatment and may have to ask permission to exercise from their physicians, adds Scott.

Astronauts, on the other hand, must complete over 300 system-wide tests ranging from clarity of vision to bone mineral density and regularly exercise before, during, and after spaceflight. In preparation for the inaugural Mercury missions, NASA postulated that “an astronaut is better prepared to withstand flight stresses if [they maintain] a state of physical fitness.” Results from subsequent missions have allowed for a better understanding of the effects of zero gravity on the human body and emphasized the importance of physical activity in minimizing decreases in muscle mass, bone demineralization, and changes in heart function (all of which are also observed in cancer patients undergoing treatment). In recent decades, NASA has developed a range of novel exercise equipment for use in microgravity and has set a strict regime for their astronauts. Following a return from space, astronauts are closely monitored and encouraged to exercise to bring their bodies back to base level.

The authors state that a tremendous opportunity exists to leverage 60 years of research conducted by NASA’s scientists to establish a program that optimizes preparation, tolerability, and recovery from a cancer diagnosis and treatment. Scott and her team believe that it’s time we start thinking about how to use NASA’s tactics to manage some of these long term side effects of cancer treatment and propose that recommending basic exercise such as walking daily on a treadmill could be highly beneficial.

While more research needs to be done to ensure that a cancer-specific countermeaures program will provide the clinical outcomes that the authors propose, “such work not only is critical given the growing burden of cancer multisystem toxicity but also has the potential to change the landscape of cancer care and management.”