Illustration: Kieran O’Brien

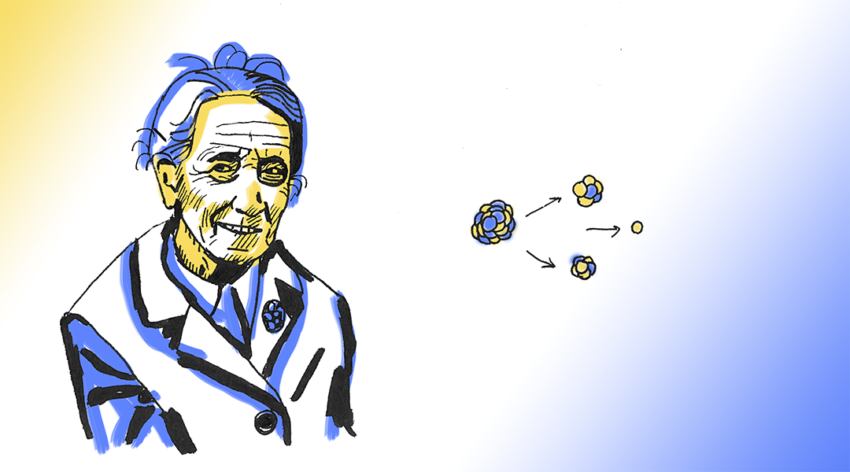

The splitting of the atom was a discovery that would change the world forever. In continuation of our Pioneers in Science series, this week we highlight Lise Meitner for her part in the discovery of nuclear fission.

Meitner was a pioneering physicist who studied radioactivity and nuclear physics, and despite being an equal member of the team that uncovered the process behind nuclear fission, her contributions were overlooked when her colleague, Otto Hahn, was awarded the 1945 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work. Though her legacy has been obscured and she has falsely been called the “mother of the atomic bomb,” (she did not directly work on its development), Meitner made revolutionary contributions to the field of nuclear physics, and is only now gaining the acclaim she has always deserved.

Early Life and Education

Meitner was born in Vienna on November 7, 1878, to Philip and Hedwig Meitner. The family of 10 was Jewish but not devout, and the couple’s children were eventually baptized Christian—though these conversions would later not be recognized when the Nazis came to power. As a result of restrictions on female education, Meitner was only able to attend university in 1897 when the University of Vienna opened its doors to women. Here, she studied under Ludwig Boltzmann where ” [he] gave her the vision of physics as a battle for ultimate truth, a vision she never lost…”, and became the second woman to graduate with a Ph.D. from the university.

She left for Berlin in 1907 to attend Max Planck’s lectures and continue her studies in physics, but was not permitted access to the laboratories of the Berlin Institute for Chemistry where she worked as an unpaid research scientist. Here, she met chemist Otto Hahn with whom she would establish a collaboration that would last over 30 years. Hahn allowed her to work in his lab and together they studied the complex physical properties of radioactive substances, presenting paradigm-shifting discoveries to the budding field of nuclear physics.

In 1910, Hahn became a professor at Berlin, and was later appointed the head of radiochemistry for the newly-established Kaiser Wilhelm Gesellschaft (KWG), where Meitner joined him as his research assistant—still, it was widely accepted that their contributions were equal.

In subsequent years, the duo suffered hardships as a result of World War I and their research was put on hold. However, by the end of 1918 the team had reunited with Meitner no longer a meager assistant but working as head of physics at KWG. She continued to make strides, becoming a full lecturer in 1922 and the university’s (and Germany’s) first female professor in 1926. While significant achievements for the time, popular opinion with regards to women taking on leading academic roles was eloquently summarized when the Berlin press referred to her inaugural lecture on cosmic physics as “Cosmetic Physics”.

Regardless, between 1924 and 1934, Hahn and Meitner gained international prestige, and during this time, the field of subatomic physics had been making significant advancements.

A Discovery That Would Change the World

In 1934, Enrico Fermi bombarded uranium atoms with neutrons (previously discovered in 1932), producing new elements which he believed to be heavier than uranium. Most scientists believed the fission or splitting of large atoms to be energetically impossible, and that hitting them with a neutron could only induce small changes.

It’s actually interesting to note that one chemist, Ida Noddack, pointed out the possibility that the products observed during Fermi’s reactions might be the result of the breaking up of uranium into lighter elements. She did not provide any theoretical evidence for her theory and her paper, published in Angewandte Chemie in 1934, was largely ignored.

Around the same time, Meitner and Hahn, along with their assistant Fritz Strassman, began conducting similar experiments in order to identify the products of Fermi’s reactions. However, their progress was again hindered when Meitner was forced to quickly flee to Sweden in 1938 as a result of her Jewish heritage, which she gratefully accomplished with the aid of the physics community. She worked again as a research assistant at the Nobel Research Institute of Physics for the rest of the war years, during which she remained in close communication with Hahn who wrote regular reports to her on their shared project.

On December 24, 1938, Hahn sent a letter to Meitner recounting a strange occurrence in which his analysis identified barium, an element with approximately half the mass of uranium, present among the uranium decay products. In his letter, Hahn asked Meitner to interpret what was happening as he could provide no plausible explanation.

When she received the letter, Meitner was being visited by her nephew, Otto Frisch, who was working in Niel Bohr’s group in Copenhagen, and aided in providing an answer.

Meitner and Frisch’s explanation proposed that one think of a nucleus as a liquid drop—a model that had been promoted by Niels Bohr—which implies that after collision with another particle, the uranium nucleus might become elongated like a water droplet, pinching in the middle and splitting into two drops (or smaller atoms). After analyzing Hahn’s results, Meitner realized that a portion of mass was still unaccounted for; since mass cannot be lost, she postulated that the missing mass had been converted to energy according to the relationship between mass and energy, E=mc2.

Frisch hurried back to Copenhagen to repeat the experiments and the two published a series of articles in Nature in early 1939, which provided a theoretical explanation for the fission of uranium. Frisch had dubbed the new process “fission” after the term “binary fission” used by biologists to describe cell division.

Hahn had also written up their findings and submitted them to Die Naturwissenschaften at the end of 1938 without crediting either Meitner’s nor their assistant Fritz Strassman’s contributions; an act that would eclipse Meitner’s role in the discovery.

The “Nobel” Mistake

In 1945, Hahn was solely awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of nuclear fission, which had required Meitner’s and Frisch’s physical insight as much as the chemical findings of Hahn and Strassmann. As a result, Meitner is often noted as one of the most glaring examples of women’s scientific achievements being overlooked by the academy.

The “Nobel mistake” was never rectified, but as some sort of reparation Hahn, Meitner, and Strassman were awarded the U.S. Fermi Prize in 1966 “for pioneering research in the naturally occurring radioactivities and extensive experimental studies leading to the discovery of fission”. She later received numerous honors from universities in the U.S., and in 1982, the element meitnerium was named in her honor.

Though it is unfortunate that Lise Meitner has been overlooked for so long, the fact that she is gaining the acclaim and recognition she deserves almost 80 years later is a testament to her brilliance and pivotal role as a pioneer in her field.

To read about other pioneers in science, you can access our Pioneers Series here.

References:

Ruth Lewin Sime: Lise Meitner: A Life in Physics, University of California Press, 1996.

O Frisch, What Little I Remember, Cambridge University Press, 1979

Rife, Patricia. Lise Meitner and the Dawn of the Nuclear Age. Boston: 1999.